Colosseum

The Colosseum (Flavian Amphitheater) is surely the most famous monument of Rome, so much so that it has come to represent the city itself, as well as the glories of the Roman Empire. This extraordinary triumph of architecture was the largest amphitheatre in the ancient world and despite being partly in ruins it still leaves visitors awestruck by its sheer size and magnificence.

Location:

Piazza del Colosseo

Built by:

Emperor Vespasian and Emperor Titus between c.70/71 C.E. - c.81 C.E.

What to see:

Colosseum, hypogeum

Opening hours:

All days, 8.30-16.30/19:15

Price:

Starting at 16 euro

Transport:

Bus. Metro station: Colosseo (B)

Tours:

Most popular tours

Top selling tickets on ArcheoRoma

The Colosseum (or Coliseum) was originally the central building within an extensive complex of structures with various functions that were closely connected to it. It was used for gladiatorial contests and various other public events and performances, and it was connected to several other buildings and structures (also by underground tunnels), including the Armamentarium, where weapons were stored.

Moreover, the Summum Choragium was used as a deposit for theatrical scenery and machinery; the Sanitarium, where wounded gladiators were treated: and the Spoliarium, where the bodies of those who died in the arena were taken to be stripped of their armour and prepared for burial.

These were converted from the gardens and the vestibule (monumental entrance) of the emperor Nero’s former palace. Also nearby was the Ludus Magnus a training school for gladiators, as well as the Ludus Matutinus, where fighters of animals were trained.

Following the death of Nero (68 C.E.) and the “year of the three emperors” (68-69 C.E.), construction of the Colosseum began under Emperor Vespasian (Titus Flavius Vespasian, who reigned from 1st July 69 C.E. to 24th June 79 C.E.) in around 72 C.E. (but planning possibly began as early as 70 C.E.) It took only about eight years to erect this massive building and the Colosseum was inaugurated in 80 C.E., under the reign of Vespasian’s son Emperor Titus.

The Colosseum was probably funded by the spoils taken from the Second Temple of Jerusalem, as well as from the conquest and sacking of the Jewish city by the legions commanded by Titus in August and September of 70 C.E. (Now only the Western Wall, or so-called Wailing Wall, of the temple still remains).

Vespasian’s radical building intervention affected the entire area that was still occupied by Nero’s Golden House, including several other buildings around the amphitheatre, which was originally called the Flavian Amphitheatre (or Amphitheatrum Flavianum), after the name of the new imperial Flavian dynasty founded by Vespasian. Some of the tunnels that ran between these buildings still survive.

The entire complex of structures covered an area of at least seven hectares, and it took about twenty years to complete them, until the end of the reign of Emperor Domitian (Titus’s brother).

Following the great fire of 18th July 64 C.E. which raged for six days and nights and destroyed a large part of the centre of Rome, the emperor Nero (Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, who reigned from 13th October 54 C.E. to 9th June 68 C.E.) had his sumptuous residence or palace, the Golden House, or Domus Aurea, built in this area which lies in the valley between the Palatine, Esquiline, Oppian and Caelian hills. There was almost certainly a large quadrangular artificial pool or lake (known as the stagnus) in the low-lying area where the Colosseum would be built.

A short distance to the west of the artificial lake was the vestibule or monumental entrance to the Domus Aurea, a large square lined with porticoes. It seems certain that this is where the Colossus of Nero (Colossus Neronis) originally stood. This was a bronze statue commissioned by Nero from the Greek sculptor and architect Zenodorus and built between 64 and 68 C.E. Pliny the Elder states that it was 106.5 Roman feet high (30.3 metres) although other sources claim it was even larger.

Suetonius, in his rather anecdotal De vita Caesarum (“Lives of the Caesars” – Vespasian 18), written prior to 121 C.E., refers to wages or rewards given by Vespasian to a restorer or repairer (refector) of the Colossus, and Martial’s words in the Liber Spectaculorum: “crescunt media pegmata celsa via” (tall scaffoldings rise in the middle of the street) might refer to scaffolding used to effect a restoration.

Pliny in his Natural History (written prior to 79 C.E.) says it was intended to represent Nero “but is now dedicated to the sun after the condemnation of that emperor’s crimes”, while Cassius Dio, in his Roman History book 65 chapter 15, section 1 (written around 211-233 C.E.) says that the Colossus was “set up on the Sacred Way” and that it had “the features of Nero …. or those of Titus”.

Finally the late Roman Augustan History (Historia Augusta – The Life of Hadrian, ch. 19) clearly states that during Hadrian’s reign, around the time of the inauguration of the temple of Venus and Roma (135 C.E.), the statue was “consecrated to the Sun, after removing the features of Nero, to whom it had previously been dedicated.” It thus seems likely that the colossus was transformed into a statue of the sun god Helios.

According to one theory the Colosseum took its name from its proximity to the Colossus of Nero, although the name “Colosseum” appears to derive from medieval times, when the Colossus probably no longer existed, having been destroyed during the Sack of Rome in 410, or by an earthquake.

Emperor Hadrian had the statue moved even closer to the Colosseum in around 128 C.E., to make space for his large building the Temple of Venus and Roma, and it was supposedly moved by 24 elephants. The original masonry pedestal of the statue was demolished in 1936 and now only its foundations remain.

A historical photograph taken in 1890 showing the base of the Colossus of Nero in front of the Colosseum.1

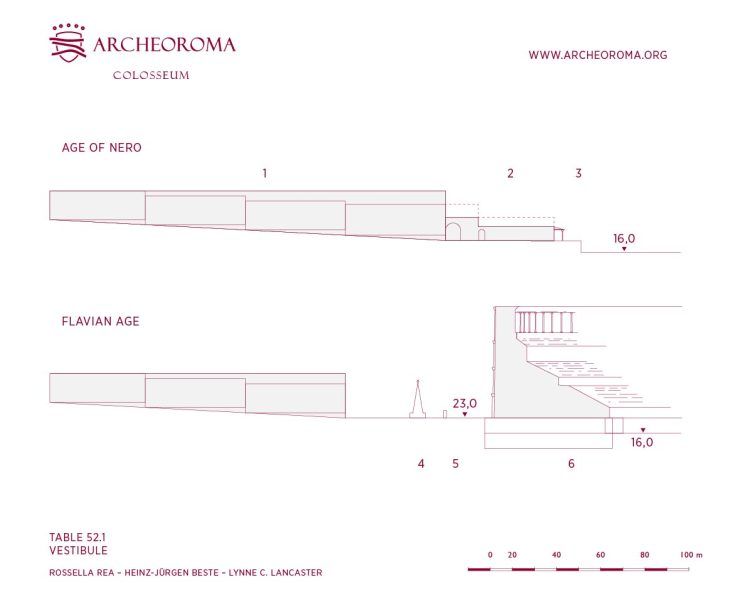

The following cross-section diagrams (based on the reconstructive research of Rossella Rea, Heinz-Jürgen Beste and Lynne C. Lancaster2) show how the appearance of the site radically changed after the Colosseum was built. It is particularly evident that the vestibule-atrium of the Domus Aurea was substantially reduced to make room for the enormous new construction.

| At the time of Nero | After the building of the Colosseum |

| 1 – Vestibule-atrium | 4 – Meta Sudans |

| 2 – Terraces | 5 – Sacred perimeter of the amphitheatre |

| 3 – Porticoes and lake | 6 – The Flavian Amphitheatre |

As we can see in the cross-sections of TAV. 52.1 (viewed from the south), the vestibule (monumental entrance) of the Domus Aurea gradually descended with terraces that terminated towards the east in a portico overlooking an artificial lake. This was supplied by the Claudian aqueduct through a nymphaeum (a water garden) and it probably covered an area larger than that of the amphitheatre, perhaps as much as four hectares, compared to the 2.4 hectares of the Colosseum.

The eastern end of the terraced area was then levelled and its buildings were demolished to make room for the Colosseum and its sacred perimeter, which was paved with large slabs of white travertine stone and delimited by vertical stones, five of which still remain standing on the eastern side. The ropes of the velarium (an awning that could be extended over the stands for protecting the spectators from the sun) are thought to have been attached to these stones.

In addition to the above-mentioned Colossus, during the reign of Titus the vestibule housed the “celsa pegmata” or theatrical machinery for the amphitheatre, which was transported directly by means of a covered passageway (a cryptoporticus) into the underground chambers of the amphitheatre. From here scenery could be raised into the arena through hatches before or even during the shows. We find confirmation of this in the poems and epigrams of Martial.3

Cassius Dio relates that when Hadrian showed the famous architect Apollodorus his plan for the temple of Venus and Roma the latter pointed out that a deeper basement should have been excavated beneath it, in order to make room for the machinery (μικανίματα) so that it could be assembled and brought into the amphitheatre unobserved.[4 Cassius Dio, Roman History book 69 chapter 4, section 3 et seq.]

Vespasian’s decision to remove many structures of Nero’s palace certainly had a political significance. By constructing an amphitheatre here for public entertainment he was in effect giving the area back to the people (as it had previously been a residential area). The site, a valley previously filled by a lake, had to be carefully drained to avoid the risk of subsidence and so several channels were dug at a depth of 8 meters through which underground water could flow away.

These channels would then be connected to a sewer system around the Colosseum which would collect the waste from public toilets in the building. Then a set of concentric foundations, mostly made of concrete, were laid, ranging from a depth of 13 meters under the outer walls to 4 meters under the central arena. These facts alone show how carefully the building was planned, even before the first stone was laid.

It has been estimated that as many as 100,000 prisoners were bought back to Rome as slaves after the Jewish War, which ended in 73 C.E. Thousands of them certainly worked under hundreds of skilled stonemasons to build the Colosseum. They would also have quarried the blocks of travertine stone at Tivoli, 20 miles east of Rome, and transported them to Rome. This whitish limestone was used to construct the basic “skeleton” of the building, consisting of the main load-bearing pillars, most of the ground floor and the entire external wall, reaching a height of 48 meters (158 feet).

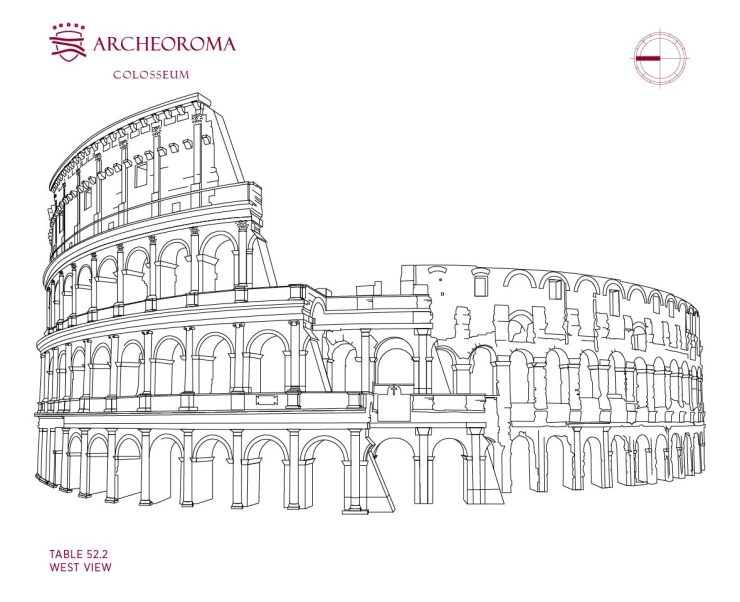

Moreover, this monumental outer wall, consisting of 3 levels, each one perforated by 80 arches, topped by a fourth “attic” level with 40 central rectangular windows, was made of over 100,000 cubic meters of travertine stone, held together by iron or bronze clamps, amounting to around 300 tons of metal. These clamps were extracted in medieval times, leaving the many small holes that can now be seen all over the building.

But travertine was not the only construction material and the lighter and softer volcanic rock known as tuff or tufo was used for minor pillars and inner walls, together with bricks for the arches. Concrete was used extensively to construct the many passageways that led up to the seating areas. These corridors were called vomitoria, because they allowed many people to quickly leave the building as if it were vomiting them out.

The use of concrete was a relatively new technology and it was still usually combined with heavier stone structures. It was made by mixing a volcanic sand or dust (pozzolana) with rubble aggregate and quicklime. Thanks to this technique the exceptionally strong and light vaulted ceilings of the corridors below the stands could be built quickly by relatively unskilled labourers. All the evidence suggests that the use of different materials and building techniques was intended to maximise the speed and efficiency of construction and the stability and durability of this extraordinary building.

Vespasian had many years of experience as a military commander in the field and he played an important role in the invasion of Britain in 43 CE. Being accustomed to dealing with swift and efficient engineers on campaign, he would certainly have expected no less from the teams responsible for building his amphitheatre. In fact they developed a new technique of making standardized and interchangeable pre-fabricated parts, such as the stairs and the marble seats. These were constructed in workshops off-site and then fitted into the amphitheatre when required.

Due to the variations in construction techniques that have been detected in different parts of the building archaeologists now think that four separate contractors each built a different quadrant of the Colosseum. They may have competed to see who could get the job done first, probably with a prize or bonus from the emperor for the winner.

According to a Roman legend the architect who planned the Colosseum was a certain Gaudentius, a Roman nobleman who then became a Christian martyr when he was killed in the arena that he himself had designed, at some time near the end of Domitian’s reign (89-96 C.E.) when Christians were supposedly being persecuted.

This fantastic legend seems to originate in the seventeenth century, and it was probably based on the erroneous interpretation of an inscription found in a crypt in the church of Saints Luke and Martina, in the Roman Forum. In fact, although, thanks to inscriptions and historical sources, we usually know who commissioned and paid for Roman monuments, the names of their architects and designers have rarely come down to us, as they were often considered as less important, like the many unskilled workers who built their creations.

Vespasian died at the age of sixty-nine on June 23rd, 79 C.E. and was succeeded by his son Titus, who made a substantial commitment to the city and people of Rome, with several public buildings. This included the continuation of work on the Flavian Amphitheatre. During his short reign the third and fourth seating levels of the building were completed. These were known as the maenianum secundum, reserved for ordinary Roman citizens and divided into the immum below, for wealthier citizens, and the summum above, for poorer citizens.

Vespasian did not live to see the spectacular inauguration of the immense construction that he had begun. This took place in 80 CE, during the reign of his son Titus and it consisted of a hundred days of festivities, consisting of gladiator fights, wild animal hunts (venationes) and, according to the poet Martial, some spectacularly cruel executions, as well as a naval battle (naumachia) and various swimming performances, during which the arena was presumably filled with water like an enormous bathtub.

When Titus died in September 81 AD his brother Domitian (Titus Flavius Caesar Domitianus Augustus), the third and last emperor of the Flavian dynasty, came to power. He made some important changes to the extensive network of subterranean areas (hypogeum) of the Flavian Amphitheatre and he completed the nearby “Meta Sudans” fountain.

Domitian had a complex system built of masonry and wooden elements to replace or improve the original underground structures. These subterranean areas had several different functions related to the shows in the area above. There were a series of rooms for wild animals, people who had been condemned to death in the arena, gladiators, and the machinery for lifting scenery and animals.

However, due to these changes it was no longer possible to flood the arena with water in order to recreate naval battles (naumachie), which in any case were held in other locations within the city. From the time of Domitian onwards, the shows in the arena were mostly gladiatorial games (munera – literally “funerary offerings”) and wild animal hunts (venationes).

An imposing fountain to the south-west of the amphitheatre, known as the Meta Sudans, was completed in the reign of Domitian. It stood about 17 meters high and had a truncated conical shape with a circular base. Some rivulets of water probably flowed from its summit, to fill a basin below that was 16 meters wide and 1.4 meters deep.

Its name derives from its shape, which was similar to that of the meta, a solid conical marker post at either end of a Roman racecourse or “circus”, around which horse-drawn chariots turned. The term sudans means “sweating”, as it seems that water oozed like sweat over the surface of the fountain, shining as it reflected the light, rather than spouting from the top.

It marked the point where four or possibly five out of the fourteen urban regions of ancient Rome (regions I, II, III, IV and X) came together. The solid brick core of the Meta Sudans, as well as the base of the colossus of Nero, still remained standing until the 20th century, but they were both demolished between 1933 and 1936 as part of Benito Mussolini’s project to create a road encircling the Colosseum at the end of the street he had built for military parades: Via dei Fori Imperiali.

The dimensions of the Colosseum:

| Height of outer wall | 48.5 meters |

| Total length | 188 meters |

| Total width | 156 meters |

| Original outer perimeter length | 527 meters |

| Dimensions of the arena | 3357 m² |

The Colosseum was the largest amphitheatre to be built during the Roman Empire. The second-largest Roman amphitheatre was located at Capua in southen Italy. This was one of the first such buildings to be made of stone, and may have been built about a hundred years before the Colosseum, which was perhaps based on its design. Its outer dimensions were 167 x 137 meters.

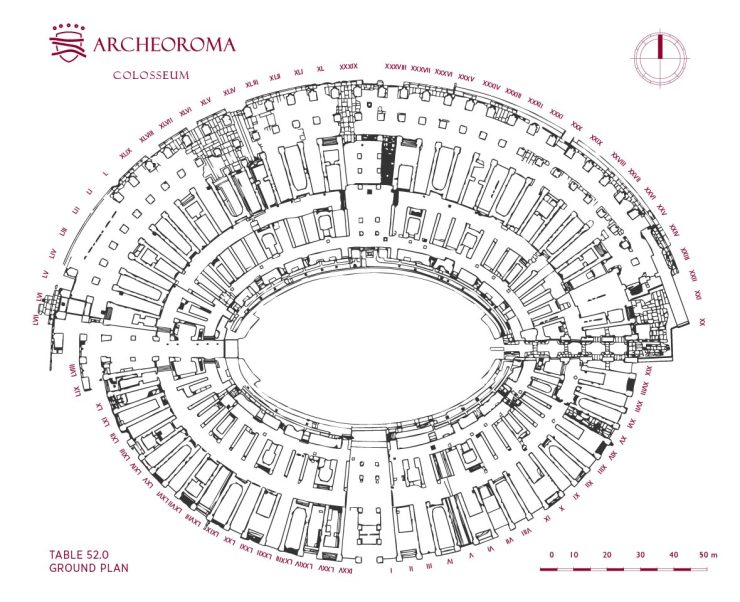

The basic structure of the Colosseum consists of eighty radial walls built upon an elliptical foundation that converge towards the arena from the outer perimeter wall. These walls support vaults, which in turn support the marble steps of the stands for spectators, or cavea.

In the external perimeter wall, between each of the radial walls, there are arches, which led to the stairways that went up to that the various sectors of the cavea. Above each of the arches that still stand today the progressive numbers of the entrances are carved, which corresponded to the tessera (“ticket” or“card”) of the spectators (see TABLE 52.0).

Ground plan of the Colosseum (Flavian Amphitheatre) The building materials of the Colosseum

The main building material for the construction of the Colosseum was travertine stone or “lapis tiburtinus” . Over a hundred thousand tons of this durable limestone were transported on wagons from the nearby quarries of Albulae at Tibur, the town now known as Tivoli, on a twenty-kilometre road that was specially made for this purpose.

An estimated seven hundred and fifty thousand tons of dressed and squared stone, eight thousand tons of marble, six thousand tons of mortar and three hundred tons of iron were also used in the building. There were also stucco decorations that embellished the wall surfaces in addition to the wood used for the floors (especially on the upper levels).

The underground foundations of the amphitheatre covered 25,298 square meters, amounting to an area of just over two and a half hectares. Several previous buildings dating up to the time of Nero were demolished to clear the space for the massive new structure and an elliptical ring was excavated which was 31 metres wide and 6 metres deep, with a perimeter of 530 metres.

This was filled with cement mixed with stones to create an enormous doughnut, mostly resting upon the clay bed of what had been Nero’s lake. Four big drains ran through it, created by casting the concrete around a structure made of oak planks. They led from the arena to the four entrances of the building on the east-west and north-south axis.

Since only one of these seems to be connected to the outgoing drain it has been supposed that the other three were intended to bring water into the arena for the naval battles or naumachiae. Perhaps they also brought water for the refreshment of the spectators.

A second layer of foundations was then laid, enclosed by an external and an internal brick wall 3 metres wide, bringing the thickness of the foundations to over 12 metres. Two gaps were left in these foundations to make space for underground tunnels on the main east-west axis of the building. It is presumed that the celsa pegmata or theatrical machinery and scenery were transported to the arena by means of the underground passage to the west.

They were normally stored in the Summum Choragium (in the area later occupied by the temple of Venus and Rome) and were raised from the hypogea (the underground spaces) through trapdoors in the wooden floor of the arena.

Above this entrance, on the surface, was the “Porta Triunphalis”, where gladiators, musicians and processions entered the amphitheatre in triumph.4 Less prestigious gladiators and those condemned to death (the damnati, or “condemned”, such as prisoners of war and criminals) entered the arena from the east via a tunnel leading from the “Ludus Magnus” training school.

This entrance corresponded, on the ground-floor, to the Porta Libitinaria or “undertaker’s gate” where dead or wounded combatants were removed. A fifth tunnel, the so-called Passage of Commodus, was excavated after the Colosseum was completed. It is decorated with stuccoes but it has never been completely explored or excavated.

To the north there was the entrance reserved for the emperor and his family, perhaps connected with a passageway leading to the Esquiline Hill, while in the south there was an entrance for important authorities, such as the senators, the Praefectus Urbi, the vestal virgins and priests.

A visit to the Colosseum is an absolute must for all tourists in the Eternal City, but also for many Romans who can find the time to rediscover this wonder of the ancient world. The ticket allows you to see the ground floor, the first floor and part of the subterranean areas (hypogeum), and now you can walk onto the partially reconstructed wooden floor of the arena.

Since December 21st 2018 the Colosseum archaeological park, also including the Roman Forum, the Palatine Hill and the Domus Aurea, the current director of which is the archaeologist Alfonsina Russo, has created a new exhibition for visitors to the Colosseum.

With the collaboration of Rossella Rea, the Roma 3 University and the German Archaeological Institute of Rome, it is a multimedia journey with films and slide-shows divided into eleven sections, which reveal the architecture of the Flavian Amphitheatre, as well as its more recent transformations, the various activities conducted inside the building in Roman times, and the impressions of travellers and artists over the ages.

On 5 June 2015 the Cultural Heritage Minister Dario Franceschini inaugurated the reproduction of one of the twenty-eight elevators which the Flavian Amphitheatre was equipped with from the time of Domitian.

Visitors to the Colosseum can now see for themselves how a complex system of pulleys, ropes and counterweights made it possible for caged wild animals such as tigers, lions, bears, wolves and deer to be lifted from the subterranean areas into the arena 8 meters higher up to emerge through a trap-door.

This “beast-lift” is now located in the underground corridor on the southern side of the arena. Unfortunately, it is only put into operation on special occasions, or during visits by VIPs. For example special tours of the Colosseum were arranged for Barack Obama in March 2014 and for Russell Crowe (the star of the film “Gladiator”) in June 2018.

Colosseum: your opinions and comments

Have you visited this monument? What does it mean to you? What advice would you give to a tourist?

Colosseum tickets