The exhibition offers a deeply revised interpretation of Salvador Dalí’s oeuvre. Through more than sixty works, the show reconstructs Dalí as an intellectual figure of rare complexity: a painter, thinker and cultural strategist who transformed both the classical tradition and the language of modernity into a system entirely his own. By engaging critically with Picasso, Velázquez, Vermeer and Raphael, Dalí emerges not as a whimsical surrealist but as a conscious reformulator of Western visual codes.

The artist and the duality of his vision

An exhibition that offers one of the most rigorous and wide-ranging reconsiderations of Salvador Dalí in recent scholarship. Bringing together paintings, drawings, archival photographs and audiovisual materials, the exhibition situates Dalí within a long durée of European art, revealing how deeply his imagination was nourished by the past even at the height of his avant-garde provocations. Carme Ruiz González e Lucia Moni, the curatorial team, makes a decisive interpretative choice: Dalí is examined not as a psychological curiosity nor as a mere eccentric of Surrealism, but as a learned and strategically self-fashioned figure, fully aware of the conceptual mechanisms that define artistic authority.

Rome serves as an ideal setting for such an inquiry. The city’s historical stratification and its centuries-long canon of artistic excellence allow Dalí’s work to be viewed within a continuum of cultural memory rather than as an isolated anomaly of the twentieth century. The exhibition reveals that Dalí did not simply “quote” the past; he transformed it into a conceptual tool. Tradition becomes for him not a constraint but a field of creative tension, a reservoir of forms, symbols and techniques that he reconfigured in the service of new expressive possibilities. Dalí treated art history as a material to be modelled, dissected and reimagined, much like a scientific object. The result is an oeuvre that is not only visually spectacular but intellectually constructed.

Dalí beyond the simplistic readings of surrealism

Salvador Dalí’s position within modern art has often been the subject of misunderstanding. He is regularly depicted as the flamboyant face of Surrealism, an eccentric genius whose surreal landscapes and melting watches epitomised dream logic made visible. Yet this stereotype, while not entirely baseless, obscures the breadth of Dalí’s intellectual ambitions. His relation to Surrealism was neither passive nor unconditional; Dalí maintained a critical distance from its doctrines, particularly its hostility toward classical form and the traditional disciplines of representation.

Dalí believed that technical mastery enhanced, rather than hindered, the expression of the irrational. He understood the unconscious not as chaos but as a territory to be explored through method, precision and visual clarity. His “paranoiac-critical method,” famously theorised by the artist himself, was deeply analytical. It sought to generate images through a process of induced associative delirium, yet always underpinned by a lucid, almost scientific control of technique. This union of delirium and discipline is one of the exhibition’s central themes: Dalí is presented as an artist whose visionary impulses never devolved into mere spontaneity.

By challenging the orthodox Surrealist repudiation of the past, Dalí carved out a position entirely his own. He refused to abandon the painterly skills that he considered essential to the craft, advocating instead for a synthesis between the modern and the classical. This synthesis yielded a body of work that is simultaneously subversive and erudite, chaotic in appearance yet undergirded by a rigorous structural logic.

Dalí’s Surrealism differs from that of his contemporaries precisely in its rootedness in art history. Where others dissolved the classical figure, Dalí reinstated it; where others sought abstraction, Dalí insisted on illusionism; where others aimed to destroy the canon, Dalí cannibalised and repurposed it. The result is a Surrealism with a backbone, a Surrealism fortified by centuries of visual culture.

A portrait as intellectual, strategist and cultural theorist

The exhibition also highlights Dalí’s capacity to position himself within broader intellectual debates. Far from being an impulsive visionary, Dalí was a voracious reader and a systematic thinker. He drew on psychoanalysis, physics, optics, mathematics, Renaissance philosophy, Catholic mysticism and emerging theories of perception. His paintings can therefore be read as activated fields of knowledge. In many respects, Dalí anticipated later discussions on visual culture, authorship, the fluidity of identity and the performative nature of the artist. He understood that modernity demanded not only stylistic innovation but theoretical self-awareness.

Dalí’s writings, manuscripts, essays, manifestos, reveal a mind constantly analysing its own processes. The exhibition amplifies this intellectual dimension by integrating archival materials that track Dalí’s thought as it unfolded over time. What emerges is a portrait of Dalí not merely as an inventor of images but as a constructor of conceptual frameworks. His paintings become nodes within larger systems of ideas.

Dalí was deeply conscious of his own public persona, treating it as an extension of his work. The moustache, the theatrical gestures, the oracular declarations, these were not trivial eccentricities but semiotic devices, strategically deployed to shape his artistic identity. In this sense, Dalí was one of the first modern artists to understand self-presentation as a form of artistic production. The exhibition thus constructs a Dalí who operates simultaneously as painter, philosopher, polemicist and performer. His oeuvre becomes a densely layered palimpsest where ideology, technique, psychology and spectacle coexist.

The exhibition structure and curatorial approach

A reading of Dalí through four great interlocutors

The curatorial structure revolves around four major figures: Pablo Picasso, Diego Velázquez, Johannes Vermeer and Raffaello Sanzio. These names do not function as mere influences. They are conceived as axes through which Dalí defined, and continually redefined, his own artistic identity. Dalí approached each master with a different strategy: rivalry with Picasso, appropriation with Velázquez, obsession with Vermeer, and philosophical contemplation with Raphael. This structure gives the exhibition a conceptual coherence that mirrors Dalí’s own method of constructing his artistic genealogy. The result is less a traditional monographic show and more an intellectual cartography, mapping Dalí’s shifting position within the canon.

Genealogical method: appropriation, distortion, invention

Dalí’s relationship to art history can be described as “genealogical” in the Nietzschean sense: a critical investigation of origins that destabilises the very notion of origin itself. He did not inherit the tradition passively; he dismantled it in order to rebuild it according to his personal logic.

Through copying, reworking and reinterpreting the masters, Dalí exposed the mechanics of artistic authority. His quotations are rarely literal; more often they are analytical, aimed at revealing structural principles that can then be stretched, inverted or exploded. Dalí enters the canon not as a disciple but as a contester, an artist who simultaneously reveres and disrupts his predecessors. This approach prefigures later practices of postmodern appropriation, demonstrating how Dalí anticipated debates that would only emerge decades later.

The four pillars of Dalí’s artistic imagination

Pablo Picasso: rival, catalyst and modern counterpart

Dalí’s relationship with Picasso is one of the most complex and fertile confrontations in modern art. Picasso represented for Dalí an unavoidable measure of artistic genius, a figure whose dominance had to be acknowledged, countered and, if possible, surpassed. Dalí’s admiration for Picasso was tinged with competitiveness. He recognised in Picasso a centrifugal force that threatened to overshadow the entire field of twentieth-century painting.

Rather than succumbing to this gravitational pull, Dalí sought to differentiate himself. His refusal to follow Picasso fully into Cubism was not an act of resistance to innovation but a critique of its limitations. Dalí believed that fragmentation of form, taken to its extreme, risked severing the image from its psychological content. For Dalí, the figure remained essential: an anchor through which interiority could be expressed.

Thus, Dalí’s engagement with Picasso became a contest of worldviews. Picasso dismantled the figure; Dalí rebuilt it. Picasso sought to break representation; Dalí aimed to distort it without rendering it unrecognisable. Their dialogue, implicit, sometimes explicit, shaped Dalí’s definition of his own position within modernity. Through this rivalry, Dalí forged a path that allowed him to combine classical rigor with avant-garde experimentation. Picasso becomes, in this sense, the revolutionary mirror against which Dalí articulated his own intellectual autonomy.

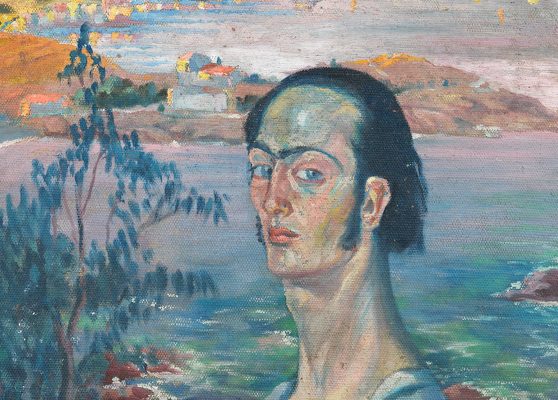

Diego Velázquez: authority, identity and the discipline of the gaze

Velázquez stands in Dalí’s pantheon as a figure of absolute authority. His technical supremacy, psychological insight and compositional mastery represented for Dalí the apex of Spanish artistic tradition. Dalí’s repeated engagement with the Velázquezian image, particularly the self-portrait, reveals a profound desire to situate himself within this lineage. Yet Dalí’s references to Velázquez are never mere homages; they are acts of symbolic negotiation. Dalí adopts the Velázquezian beard and moustache not as mimicry but as a deliberate strategy of self-inscription. He transforms an emblem of classical dignity into an instrument of surrealist irony, weaponising tradition to construct a new persona.

In Dalí’s reinterpretations, Velázquez’s solemnity is filtered through a surrealist lens. Shadows elongate, spatial coherence dissolves, and the psychological tension of the original becomes amplified into an almost metaphysical drama. The clarity of Velázquez becomes for Dalí a foundation upon which he can stage controlled unravelings of reality. Dalí considers Velázquez not only a painter of appearances but a theorist of vision, someone who understood the gaze as a political, ontological and aesthetic device. Dalí seizes upon this insight, extending it into a domain where the gaze becomes unstable, recursive and paranoiac. Velázquez thus becomes a conceptual partner, enabling Dalí to explore the performative and self-reflective dimensions of image-making.

Johannes Vermeer: light, stillness and the obsession with perfection

Vermeer occupies a more intimate and cerebral space in Dalí’s imagination. His meticulously controlled light and geometric serenity offered Dalí a model of visual precision bordering on the metaphysical. Dalí approached Vermeer with a mixture of reverence and analytical fervor. He sought not to imitate Vermeer’s style but to decode the mechanisms that produced it. Vermeer’s restrained compositions became, under Dalí’s scrutiny, sites of intense psychological and perceptual inquiry.

Dalí’s repeated reinterpretations of The Lacemaker illuminate this obsessive engagement. By magnifying, fragmenting or displacing the lacemaker within dreamlike architectural spaces, Dalí exposes the uncanny dimension latent in Vermeer’s stillness. The silent domestic interior becomes a theatre of subconscious energies; the precise fall of light becomes a metaphysical event. Dalí uses Vermeer as a prism through which to explore the tension between order and delirium. What appears calm becomes charged; what appears stable becomes tremulous. Through Vermeer, Dalí expands the vocabulary of Surrealism, demonstrating that the uncanny can arise not only from chaos but from excessive harmony.

Raffaello Sanzio: ideal beauty, harmony and the architecture of thought

If Velázquez and Vermeer provide Dalí with models of psychological and perceptual complexity, Raphael offers him a framework for understanding beauty as an intellectual construct. Raphael’s idealization of the human figure, his clarity of composition and his serene proportions represent for Dalí a classical cosmology: a system in which aesthetic balance reflects metaphysical order. Yet Dalí’s relationship with Raphael is far from devotional. He recognises the ideological dimension of Raphael’s harmony, its reliance on symmetry, proportion and the disciplined body, and treats it as an analytical structure, not a dogma.

Dalí’s adaptations of Raphael often involve calculated distortions: limbs elongate, faces fracture, compositions tilt. These alterations are not capricious but philosophical. They reveal that classical ideality is not a natural given but an assemblage of rules that can be dismantled. Raphael becomes for Dalí a laboratory for interrogating beauty itself. By destabilising Raphael’s harmony, Dalí exposes the tension between ideal form and human desire. He redefines Beauty not as immutable but as mutable, elastic, and susceptible to the same paranoiac shifts that govern the subconscious. Raphael thus serves as a fulcrum for Dalí’s synthesis of the rational and the irrational. Tradition becomes a structure through which new mental landscapes can emerge.

Dalì: visionary and cultural reformer

Dalí as a Re-Coder of modern art

Perhaps the most original contribution of the exhibition is the way it positions Dalí as an artist who reformulated the codes of modern art. Dalí understood that the twentieth century demanded new forms of visual communication, but he also understood that innovation requires memory. He rejected the false dichotomy between past and present, proposing instead a dynamic continuum in which historical forms are constantly reinterpreted. Dalí’s Surrealism, therefore, becomes a vehicle for reprogramming modernity: he reinjects technical rigor into an avant-garde that had forsaken it; he reintroduces narrative into movements that sought its dissolution; he reclaims craft in an era obsessed with rupture. Dalí redefines modernity not as an escape from tradition but as the perpetual reinvention of tradition.

Intellectual: thinker, reader, architect of ideas

The exhibition foregrounds Dalí’s intellectual persona to a degree rarely seen in public presentations. His notebooks and writings reveal an artist grappling with questions of ontology, representation, science and metaphysics. He was fascinated by theories of relativity, by the structure of DNA, by the fourth dimension, by the psychology of fetishism, by the mechanics of optics. These diverse interests converge in his painting, where scientific speculation and classical form intertwine. Dalí’s capacity to synthesise disparate fields into unified visual statements marks him as one of the twentieth century’s most intellectually ambitious artists. He does not merely illustrate ideas; he transforms them into aesthetic events.

Performer and Constructor of the Self

No portrait of Dalí would be complete without acknowledging the theatricality of his persona. Yet the exhibition avoids reducing this to eccentricity. Instead, it highlights the performative dimension of Dalí’s identity as a sophisticated artistic tool. Dalí’s public appearances, his moustache, his enigmatic declarations, all these elements form a semiotic system that complements his visual art. Dalí recognised that in the modern world, the boundary between artwork and artist is porous. By crafting his persona with calculated precision, Dalí expanded the field of artistic action beyond the canvas. The artist, for Dalí, becomes an image-producing machine whose own body and behaviour participate in the construction of meaning.

Legacy as a critical thinker

What the exhibition ultimately reveals is a Dalí whose legacy exceeds the boundaries of Surrealism and even painting itself. He stands as a cultural theorist who anticipated many of the concerns of contemporary art: the instability of identity, the performativity of authorship, the dynamics of appropriation, the critique of originality, the tension between image and ideology. Dalí’s oeuvre becomes a laboratory for exploring these questions, a space where tradition and revolution collide in complex, unpredictable ways. Seeing Dalí through this prism allows us to understand the modernity of his work not as an eccentric deviation but as a profound rethinking of what it means to make art in the twentieth century.