30 January - 29 June 2026

This comprehensive overview of the work of Irving Penn, one of the central figures of 20th-century photography, spans nearly seventy years. Through a meticulous selection of images, the exhibition explores the evolution of a visual language that profoundly influenced fashion photography, portraiture, and still life, highlighting the photographer’s ability to combine formal rigor and conceptual depth.

Piazza Orazio Giustiniani, 4

Spanning works produced between 1939 and 2007, this major retrospective presents 109 photographs by Irving Penn, offering a focused overview of a visual language that shaped modern photography. Drawn from the collection of the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris, the selection brings together fashion, portraiture, travel series, nudes, and still lifes, highlighting Penn’s formal rigor and his decisive role in affirming the photographic print as a site of lasting artistic value.

Conceived as a coherent curatorial statement rather than a mere anthology of iconic images, the exhibition emphasizes Penn’s disciplined use of form, restraint, and surface, presenting photography as a material and conceptual practice in which the print remains central to meaning.

Penn’s position in twentieth-century photography derives from a rare synthesis: the ability to work within the circuits of magazines and commissions while continuously pushing toward a rigorous, almost philosophical exploration of form. His early training in design endowed him with a structural sensibility, a capacity to think in terms of volumes, planes, margins, and intervals. In his photographs, the frame is never neutral; it is an architecture that governs the viewer’s attention, staging a measured encounter between eye and subject.

To speak of Penn’s “rigor” is not to invoke coldness or detachment. Rather, it is to name a method of concentration. He reduces the scene to essential components so that the smallest variations, an angle of a shoulder, the tension of a hand, the grain of fabric, the soft resistance of skin, become meaningful. This discipline is particularly striking in his portraits and fashion photographs, where the minimal backdrop is not a void but a pressure field that intensifies presence.

Many of Penn’s best-known images operate through an apparent economy: a subject, a controlled light, a limited tonal scale, a background that refuses distraction. Yet behind this apparent simplicity lies a complex apparatus of choices. The reduction of environment is not a denial of context, but a way to suspend it, allowing the subject to appear in a state of heightened legibility. In this sense, Penn’s studio becomes a laboratory of visibility, where representation is continuously recalibrated through the discipline of framing.

The exhibition insists on Penn’s stature not only as a photographer but as a master printer. This aspect is decisive for understanding why his images endure beyond the circumstances of their production. Penn followed each stage of the process with obsessive care, experimenting with refined techniques such as platinum printing and, for certain still lifes, sumptuous platinum-palladium prints. These processes are not secondary “technical” details: they embody a conception of the photographic image as a material object with its own temporal depth.

In an era when photography risks becoming pure circulation, images detached from their supports, Penn’s insistence on printing is a form of resistance. The print becomes a site where the image’s authority is not merely visual but physical: tonal gradations are anchored in matter; blacks do not collapse into emptiness; highlights are not glare but structured light. Seen in this way, Penn’s work offers a pedagogy of looking, teaching the visitor how to perceive differences of surface and density.

One of Penn’s most consequential achievements is his ability to disrupt conventional hierarchies between “high” and “applied” genres. His long association with Vogue positioned him at the heart of fashion’s visual economy, yet he consistently treated editorial work as an arena of aesthetic research. In his hands, fashion photography becomes less a theatre of glamour than a study in structure: garments are volumes; bodies are lines; poses are sculptural solutions to compositional problems. The fashion image is thus redefined as a form of modern formalism with profound cultural effects.

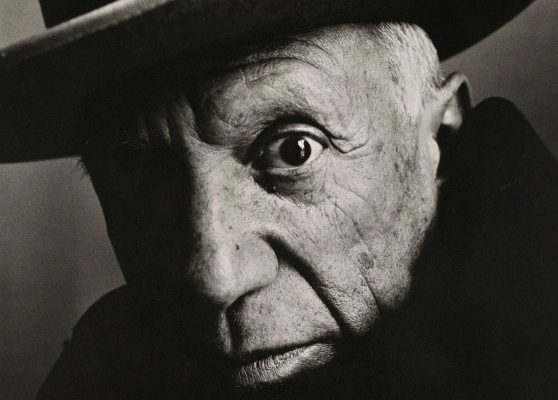

Portraiture, likewise, is reframed. Penn photographs famous figures and ordinary people with a comparable intensity, refusing the easy rhetoric of celebrity. In his studio portraits, the subject is not narrated; it is confronted. The viewer is invited to read presence rather than biography, to observe the subtle negotiations between sitter and camera. This approach does not erase individuality; it intensifies it by stripping away the decorative apparatus of identity.

Penn’s portraiture is often described as psychological, yet its psychology is not delivered through anecdote. It is constructed through stance, gaze, and the delicate balance between exposure and reserve. The neutral backdrop becomes a stage where the sitter cannot hide behind objects or environments. This mechanism produces portraits that feel both intimate and rigorous: the subject appears as if held by the frame, compelled into visibility.

Penn’s still lifes extend this logic of concentration into the world of objects. Here, the photographer’s intelligence operates through staging and subtraction: he removes the superfluous so that matter can speak. Yet his objects are not merely elegant. Penn often chose subjects that appear, at first glance, insignificant, even repellent: cigarette butts found on the street, used chewing gum, discarded remnants. Through his camera and his printing, these materials are transfigured into images of unexpected gravity.

This transfiguration is not sentimental. It is closer to a modern reactivation of the classical tradition of vanitas and memento mori, where objects carry the trace of time and mortality. Penn’s still lifes insist that modernity’s detritus is not outside the domain of representation; it is precisely where representation must prove its seriousness. In these images, waste becomes structure, decay becomes tonal architecture, and the mundane becomes a site of philosophical reflection.

It is tempting to read Penn’s still lifes as exercises in aestheticizing the ugly. Yet the deeper claim is ethical: to look carefully at what is normally disregarded. Penn’s images ask viewers to reconsider the hierarchy of attention, what deserves to be seen, and how seeing can become a form of respect. In this sense, the still life is not a decorative genre; it is a discipline of perception.

The curatorial direction is by Pascal Höel (Head of Collections, MEP), Frédérique Dolivet (Deputy Head of Collections, MEP), and Alessandra Mauro (Curator, Centro della Fotografia, Rome). The exhibition is structured into six sections, offering a comprehensive overview of Penn’s oeuvre, highlighting his mastery as a printmaker. The selection of 109 prints, spanning the years from 1939 to 2007, creates a historical and analytical journey.

This curatorial approach also underscores a key aspect of the show’s identity: its anchoring in a major European collection and in the continuity of a relationship with Penn, extended through the Irving Penn Foundation. For the visitor, this implies a privileged access to works selected not only for iconic status but for their capacity to illuminate Penn’s method: his attention to the studio as an apparatus, his willingness to experiment with printing, and his insistence on the controlled economy of the frame.

The path opens with Penn’s early photographs made between 1939 and 1947. These images, taken along the streets of New York, later in the southern United States, and in Mexico in 1941, reveal a photographer already attentive to the drama of the everyday. Here, the world is not yet fully transformed into the laboratory of the studio, but the principles that will govern Penn’s later work are already present: compositional restraint, an instinct for the eloquence of surfaces, and an ability to extract form from contingency.

A crucial episode appears in 1945, when Penn is in Europe and in Italy as a volunteer ambulance driver for the American army. He uses his camera to gather visual testimonies of a troubled period. This detail adds historical density to the retrospective: Penn’s modernism is not an abstract style floating above history, but a discipline that can confront the world’s fractures without surrendering to sensationalism.

These early photographs demonstrate that Penn’s “classic” look is not simply a late refinement. Even when working outside the studio, he seeks a kind of formal clarity that stabilizes the image against the noise of circumstance. The early works become, in the exhibition, a lens through which later series can be reread: the studio is not a departure from reality, but a method for intensifying it.

The second section is dedicated to Penn’s travels between 1948 and 1971, undertaken largely for Vogue and spanning geographies from Peru to Nepal, from Cameroon to New Guinea. These works are often described as ethnographic, yet their logic is not that of reportage. Penn isolates his subjects from their environment, placing them in a neutral space and photographing them in natural light. The effect is paradoxical: by removing context, he intensifies presence.

Here, the ethical stakes of representation become visible. Penn refuses the exoticizing rhetoric that so often accompanies images of “elsewhere.” Instead, he constructs portraits that insist on the individuality of each subject. The neutral background becomes a tool of equality: it does not flatten difference, but prevents difference from being consumed as spectacle. Visitors are invited to consider the tension between isolation and dignity, how the photographic frame can both extract and honor.

By isolating subjects, Penn dismantles the picturesque. The viewer cannot rely on landscape, costume, or environment to “explain” the subject. Instead, the encounter is direct. This strategy, so central to Penn’s studio portraits, here becomes a critique of the ethnographic gaze, offering a more rigorous and less voyeuristic form of looking.

The third section focuses on Penn’s portraits, produced between 1947 and 1996, and largely realized in his studio, where he builds sets that are as discreet as they are decisive. Here, Penn’s language reaches a mature clarity. Celebrities, artists, writers, and cultural figures are photographed with a sobriety that resists ornament. The studio functions as a controlled environment where the subject’s presence can be measured against the frame’s logic.

Within this section, a particularly meaningful Roman node is highlighted: Penn’s photograph of a “group of Italian intellectuals at Caffè Greco,” made in Rome for Vogue in 1948. This image is more than a local curiosity; it signals Penn’s capacity to register cultural networks without resorting to illustration. The group portrait becomes a meditation on social presence, how individuals occupy space together, how identities cohere through proximity, and how the camera can render a milieu without turning it into anecdote.

The Caffè Greco photograph introduces Rome not merely as backdrop but as a site of intellectual configuration. It also enriches the exhibition’s resonance for local audiences: Penn’s modernism intersects with the city’s cultural history, suggesting how international visual culture and Roman social life briefly align within a single editorial commission.

The fourth section presents a personal series of female nudes made between 1949 and 1967. Penn selects professional models for painters and sculptors and frames the bodies as closely as possible, never showing faces. The choice is revealing: the nude here is not erotic narrative but sculptural study. Bodies become volumes; skin becomes surface; the image becomes an investigation into proximity and abstraction.

Penn’s work on these photographs extends into printing, where he subjects negatives and prints to experimental techniques, bleaching and reworking until obtaining diaphanous tones that vary from print to print. This variability matters: it insists that the photograph is not a fixed image but a field of interpretive decisions. The nude series thus becomes an inquiry into the limits of photographic reproducibility, highlighting the uniqueness of the print.

By excluding faces, Penn shifts attention from identity to form. This is not depersonalization; it is a conceptual gesture that repositions the nude within a history of sculpture and drawing. The viewer is compelled to read body as structure, an approach that aligns with Penn’s broader project of elevating photographic subjects through formal discipline.

The fifth section, spanning 1949 to 2007, addresses fashion and beauty as an essential component of Penn’s work for Vogue. Here, the retrospective demonstrates how Penn revolutionized fashion photography by treating it as a domain of compositional research. The model is not merely a carrier of garments; she becomes a sculptural presence. The garment is not decorative; it becomes architecture. The studio, again, is the condition that makes this rigor possible.

Penn’s fashion images are often celebrated for elegance, but the exhibition encourages a more analytic reading: elegance is the surface effect of a deeper discipline. Penn’s reduction of background, his orchestration of light, and his insistence on pose create images in which fashion becomes a language of forms rather than a catalogue of trends. This is one reason the photographs remain contemporary: they do not depend on the rhetoric of novelty; they depend on structure.

A revealing episode within Penn’s creative range emerges in 1967 with his work for the Dancers’ Workshop of San Francisco. Rather than illustrating a specific choreography, Penn chooses a freer interpretation of bodies in motion, performers moving, in a sense, to be photographed. The sequence reveals Penn’s ability to translate movement into photographic structure, suggesting that his studio logic is flexible enough to accommodate dynamism without abandoning compositional control.

The final section, dedicated to still life from 1949 to 2007, provides one of the most compelling reasons to the visit. Penn demonstrates extraordinary creativity in staging inanimate objects, driven by a constant determination to remove the superfluous. His still lifes often include references to vanitas and memento mori, granting his images a resonance that links modern photographic practice to older artistic traditions.

Within this section, Penn’s attraction to marginal subjects becomes central. He turns his attention to objects that appear banal or repugnant, cigarette butts, chewed gum, street detritus, and “glorifies” them through lavish platinum-palladium printing. The effect is not sensational; it is soberly transformative. The viewer is invited to confront a modern material culture where waste is omnipresent, and to consider how photography can make visible what modern life habitually erases.

These images enact a radical redistribution of attention. The still life becomes an ethical genre: to see carefully is to acknowledge existence. Penn’s insistence on printing, surface, and tonal depth reinforces this ethic, turning each work into a material argument for the seriousness of looking.

This exhibition is not only important because it gathers iconic works; it matters because it clarifies the principles that make Penn’s photography historically decisive and still intellectually productive. In an environment saturated with images, Penn’s practice proposes an alternative temporality: a slow, concentrated form of vision in which each photograph becomes a structured encounter. Visitors will leave with a sharper awareness of how framing, light, and printing shape meaning.

For those interested in the history of fashion photography, Penn represents a pivotal chapter: his studio austerity rewrote the genre’s language and continues to influence contemporary practice. For those drawn to portraiture, it offers a profound meditation on presence and dignity, on how a subject can appear without the noise of narrative. For those interested in still life, Penn’s work demonstrates that objects can have a metaphysical weight and that the photographic image can reactivate classic themes within modern material culture.

As the inaugural major event of the Centro della Fotografia di Roma, the project also marks a significant moment in the city’s cultural landscape, positioning Rome as a site where photographic culture is presented with the seriousness typically reserved for other artistic disciplines. Promoted by Roma Capitale and Fondazione Mattatoio and organized by Civita Mostre e Musei, the exhibition frames Penn not as a “photographer of style” alone, but as a central author of modern visual thought.

Your opinions and comments

Share your personal experience with the ArcheoRoma community, indicating on a 1 to 5 star rating, how much you recommend "Irving Penn. Photographs 1939-2007. Centre for Photography of Rome"

Similar events