21 November - 12 April 2026

A journey through places of leisure, power and urban memory via around 190 paintings, watercolours, prints, documents and maps: the villas and gardens of Rome as depicted by artists, architects and urban planners who captured their essence.

Museo di Roma a Palazzo Braschi, Piazza San Pantaleo, 10 e Piazza Navona, 2

The exhibition adopts the Roman garden as a privileged lens through which to understand the city’s evolution. From the sixteenth century onward, suburban villas—often commissioned by popes, cardinals, and leading families—served as places of political and cultural representation, where the design of the Italian formal garden, geometric and ordered, staged human dominion over nature. In the Baroque seventeenth century, green spaces became true scenographic devices animated by fountains, statues, pavilions, and calibrated perspectives, while the eighteenth century introduced a freer sensibility influenced by European landscape taste.

The nineteenth and twentieth centuries, by contrast, mark the growing tension between conservation and urban transformation: the expansion of the capital and major infrastructural works profoundly altered the relationship between villas, the river, and the urban fabric, while at the same time inaugurating a new season of public parks and promenades. The exhibition highlights how, over time, the garden shifted from an elite status symbol to a shared asset and a central theme in debates on urban greenery, culminating in the era of modern planning, when figures such as Luigi Piccinato redefined the city’s landscape—also documented in the paintings of Carlo Montani.

The first section is devoted to the 16th century villas, when Rome, emerging from the crises of the late Middle Ages, reasserted itself as a European artistic capital. Here the garden is still closely linked to the humanistic ideal of otium: a place for study, conversation, and antiquarian collecting, articulated through terraces, pergolas, parterres, and groves designed with strict perspectival order. The visitor is introduced to contexts such as Villa Madama, Villa Giulia, the Vatican Belvedere, and the Farnesina, documented by views and engravings that capture the moment when the Roman landscape began to be systematically designed and represented.

A central role is given to the works of Hendrick van Cleve, whose views of cardinal villas in Rome anticipate an analytical reading of green spaces, with careful attention to the placement of sculptures, architectural backdrops, and the relationship between architecture and vegetation. In his paintings, the garden is not merely a background but an organising structure: a network of axes and focal points guiding the viewer’s gaze towards loggias, exedrae, and fountains. Sixteenth-century villa iconography thus emerges as a fundamental repertoire for the history of the European garden, with Rome playing the role of a privileged laboratory.

At this stage, the Roman garden is still deeply connected to antiquarian culture: statues, fragments, and inscriptions are integrated into green spaces, transforming the villa into an open-air museum. The exhibition shows how these choices were not mere ornaments, but true instruments of self-representation, constructing a symbolic continuity between ancient Rome and the new Rome of popes and cardinals.

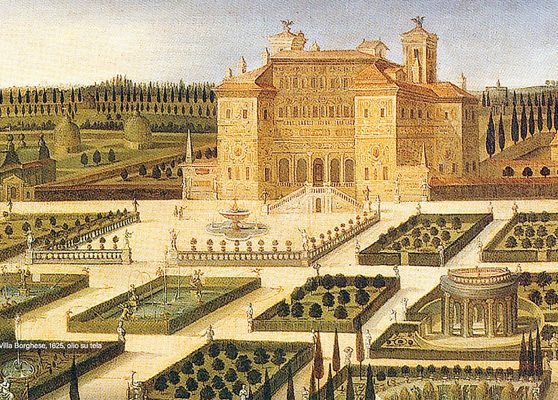

In the 17th century, Roman Baroque decisively reshaped the image of villas. Gardens became stages of papal and aristocratic power, articulated through perspectival axes, staircases, water features, and sophisticated hydraulic devices. In this context, the exhibition highlights the views of Joseph Heintz the Younger, author of celebrated depictions of Villa Borghese and Villa Mattei, which record with almost topographical precision the structure of gardens and architecture.

Heintz’s canvases, though rooted in Northern traditions, fully engage with Roman Baroque aesthetics: tree-lined avenues open onto statue-filled piazzas, parterres are punctuated by basins and fountains, and casino buildings overlook carefully staged vistas. The artist combines the precision of relief with clear light, which restores the atmospheric quality of gardens at dawn or in the middle of the day, transforming the view into a privileged tool of knowledge and representation.

Alongside Heintz, the section recalls the work of the great Baroque architects and sculptors who shaped these spaces, from Flaminio Ponzio to Carlo Maderno, from Giovanni Vasanzio to Alessandro Algardi and Pietro da Cortona, making it clear that the garden is the result of interdisciplinary collaboration between designers, artists and clients. The exhibition also highlights how the Baroque view, although originally created as a document, tends to dramatise perception, emphasising the scenic effects of the paths and views of the surrounding landscape.

The section devoted to the 18th century illustrates the transition from the rigidity of the Italian formal garden to the gradual openness of the landscape garden. Central figures are the vedutisti who acted as visual chroniclers of Rome’s gardens and their relationship with the city. Particularly prominent are the works of Caspar van Wittel, whose views of Villa Altoviti, of Villa Medici and the Tiber’s banks record not only garden layouts but also transformations brought about by major hydraulic and infrastructural works.

Alongside van Wittel, the exhibition highlights paintings by Paolo Anesi, characterised by a softer luminous sensibility, and engravings and views by Francesco Panini, whose activity was crucial in disseminating images of Roman gardens across Europe. His depictions of the Vatican Belvedere Gardens, Villa Albani, and other complexes skilfully illustrate the structure of the flowerbeds, the arrangement of the statues and the sequence of the fountains, making the garden a text that can be read through graphics.

In this context, works by Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg, such as the view of the Villa Borghese garden or the so-called ‘Casinò di Raffaello’, testify to the interest of Northern painters in the Roman landscape, perceived as a synthesis of antiquity and nature. The eighteenth-century view thus acquires an international dimension: Rome became a favourite destination on the Grand Tour, and its gardens, with their architecture immersed in greenery, became icons of a reinvented classicism that would have a lasting influence on European landscape culture.

The section on the 19th century addresses one of the most complex chapters in the history of Roman gardens:destruction, new gardens and the transformation of the city into the capital of the Kingdom of Italy, with the profound urban changes that this entailed. The opening of new roads, the construction of the Tiber embankments, and the subdivision of many suburban villas led to the loss or mutilation of numerous historic complexes. Nineteenth-century views, often created by foreign painters and travellers, oscillate between the desire to document what survives and a subtle nostalgia for a landscape perceived as threatened.

The exhibition shows how, during this period, the garden increasingly took on the role of public space. New urban parks, scenic walks and tree-lined avenues for public use are emerging, in which the villa loses some of its elitist character. The political dimension of green spaces emerges strongly: the capital city also needs to represent itself through a network of open spaces, capable of mediating between historical memory and urban modernity.

In this context, the exhibition focuses on gardens that became the scene of historical events, such as the Janiculum during the Roman Republic of 1849, and on views in which the landscape is marked by traces of conflict, transformation and construction sites. The image of the nineteenth-century garden is no longer just an ode to beauty, but also a commentary, sometimes implicit, on the tensions of modernisation.

The section entitled Living in the Villa forms the most vivid and narrative core of the exhibition. Here the garden is analysed as a lived space shaped by social rituals and daily practices. Paintings depict outdoor festivities, concerts, promenades, carriages along tree-lined avenues, children at play, and elegant figures lingering on panoramic terraces. The garden becomes a stage of urban modernity, where new forms of sociability and leisure unfold.

Particularly significant are the paintings by Georges Paul Leroux and Armando Spadini, which translate this experience into images dense with atmosphere. Leroux, author of works such as Passeggiata al Pincio (Walk in the Pincio) and the view of the Gardens of Villa d’Este in Tivoli, focuses his attention on the flow of figures, tree-lined avenues, and the relationship between green spaces and architecture, making the garden a stage for bourgeois life between the 19th and 20th centuries.

Spadini, for his part, dedicated a series of paintings to Villa Borghese and Pincio, including Trees in Villa Borghese and Music at Pincio, in which the landscape is rendered with vibrant, concise brushstrokes that capture the light filtering through the foliage, the flow of carriages and the discreet swarm of passers-by. In these works, the garden becomes almost an emotional protagonist: no longer a simple backdrop, but a pulsating organism in which urban nature reflects moods, memories and affections.

The section shows how the images of Leroux and Spadini contribute to consolidating a modern imaginary of the Roman garden, in which the dimension of pleasure and socialising is intertwined with the awareness of living in a historically determined landscape. Visitors are invited to recognise in the avenues, terraces and tree-lined backdrops depicted in these canvases places that are still frequented today but are steeped in historical and artistic resonance.

The last section deals with the 20th century, when the issue of urban greenery became an integral part of urban planning and contemporary thinking. Alongside the paintings, there are photographs, documents and references to key figures in Roman landscape culture, such as Raffaele de Vico and Luigi Piccinato.

The press release highlights the presence in the exhibition of a historic photograph of Piccinato’s miniature model of a Roman villa from the 17th and 18th centuries, demonstrating how the urban planner looked to the historical tradition of gardens as a source of inspiration for modern design.

The works documenting the gardens designed by De Vico, such as Villa Glori, Parco della Rimembranza and other 20th-century complexes, are accompanied by paintings by Carlo Montani, who meticulously depicts avenues, tree arrangements and urban views in transformation, offering a valuable visual repertoire of the evolution of Roman greenery between the 1920s and 1930s. In this dialectic between design and image, the exhibition highlights how the garden is no longer just an aristocratic heritage, but a central theme of urban modernity, the subject of public policies and theoretical reflections, as also demonstrated by Piccinato’s critical work on “modern gardens”.

The 20th-century section ideally concludes the exhibition by bringing attention back to the present: images of historic gardens, traces of their transformations, and the projects that have marked their survival or loss invite visitors to reflect on the current state of Rome’s green spaces and the shared responsibility for their protection. Through this chapter, the Museum of Rome presents itself not only as the guardian of the past, but also as a place where landscape heritage becomes a living subject for civic reflection.

One of the most significant aspects of the event is its ability to weave together different ways of seeing—Italian and foreign, painterly and graphic, historical and modern—around a single subject. In the sixteenth century, Hendrick van Cleve inaugurates a tradition of analytical observation of the cardinal’s garden, in which the arrangement of statues and architectural features within the greenery becomes a pretext for exploring new perspectival constructions. In the seventeenth century, Joseph Heintz the Younger translates the Northern legacy of the view into a Baroque key, conveying the complexity of ensembles such as Villa Borghese and Villa Mattei.

The eighteenth century witnesses the rise of the vedutisti Caspar van Wittel, Paolo Anesi, and Francesco Panini, who document the layout of Roman gardens—from Villa Medici and Villa Altoviti to the Farnesina, from the Vatican Gardens to Villa Albani—with a gaze that is at once descriptive and interpretative, poised between topography and invention. In dialogue with these masters, the Danish painter Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg, in the early nineteenth century, offers measured and luminous variations on Villa Borghese and the suburban complexes, anticipating a modern sensibility for the atmospheric perception of landscape.

With the transition to the 20th century, the representation of the garden takes on new tonalities with Georges Paul Leroux and Armando Spadini: the former attentive to crowd dynamics and to the monumental scale of the avenues of the Pincio or the gardens of Villa d’Este, the latter focused on the rhythm of trees, the filtration of light, and the everyday scenes of Romans seeking leisure and respite in the city’s parks.

In parallel, the planning culture of Luigi Piccinato and the painting of Carlo Montani testify to how the theme of the garden definitively enters the urban-planning discourse and the civic consciousness of the city, becoming an object of planning, critique, and visual memory.

Visiting the exhibition means gaining a privileged instrument for understanding how the city has been shaped, over centuries, also through its green landscape. For the first time, the exhibition offers a broad, scientifically grounded synthesis of the pictorial imagination of Roman gardens from the sixteenth century to the second half of the twentieth century, through a core group of roughly 190 works drawn from major Italian and international institutions and from private collections.

For a specialist audience—scholars, art historians, guides, and devotees of Rome—the itinerary is a rare opportunity to compare, within a single context, different languages—painting, graphic arts, photography, and documents—that together delineate the history of the garden as a place of power, otium, and representation, but also as a space of everyday life and urban design.

For non-specialist visitors, the exhibition offers a concrete key for reading the contemporary city: recognising in the historical views the same avenues, terraces, and arboreal “wings” that still shape the experience of Rome today means retying the thread between personal experience and the city’s long historical duration.

The exhibition is curated by Alberta Campitelli, Alessandro Cremona, Federica Pirani, and Sandro Santolini, with the support of an international scientific committee. It is promoted by Roma Capitale and the Capitoline Superintendence for Cultural Heritage, and produced by Zètema Progetto Cultura, with the contribution of Euphorbia Srl, Cultura del Paesaggio.

Your opinions and comments

Share your personal experience with the ArcheoRoma community, indicating on a 1 to 5 star rating, how much you recommend "Ville e giardini di Roma: una corona di delizie"

Similar events