27 February - 29 June 2025

The extraordinary exhibition dedicated to Pablo Picasso opens in Rome from February 27 to June 29, 2025. A unique opportunity to explore the trajectory of an artist who revolutionized the history of art, highlighting his status as a “foreigner” in French territory.

Museo del Corso – Polo Museale – Palazzo Cipolla, Via del Corso 320

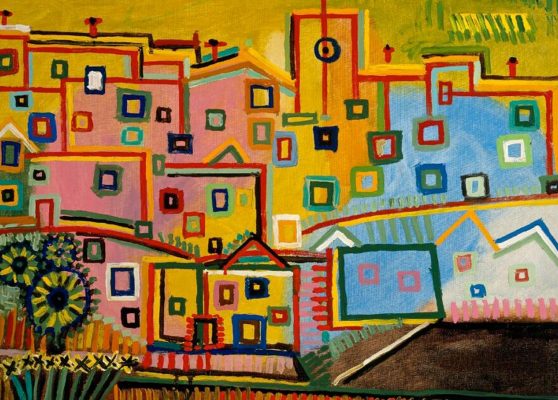

The new exhibition titled “Picasso the Foreigner” offers a journey through over half a century of Picasso’s creative activity, an artist capable of revolutionizing 20th-century painting and audaciously integrating diverse artistic languages. On view at the Museo del Corso – Polo Museale – Palazzo Cipolla in Rome from February 27 to June 29, 2025, the show explores how Picasso’s status as an outsider influenced his artistic path, from his early engagement with the Parisian avant-garde to the later stages of his prolific career. Featuring prominent works, some rarely loaned, the exhibition illustrates the metamorphosis of an artist deeply rooted in European traditions who constantly reinvented himself while preserving his independent spirit.

Pablo Picasso’s artistic journey stands at the crossroads of cultures and research that defined the early 20th century. Born in Málaga, Spain, in 1881, he grew up surrounded by aesthetic stimuli marked by both tradition and a desire for renewal. As a youth, he engaged with Barcelona’s cultural ferment, meeting intellectuals and artists intent on breaking with academic conventions. Yet it was his definitive move to Paris that proved crucial in shaping a wholly personal pictorial language, born of constant confrontation with international art and a wide range of formal experiments.

Although profoundly Spanish in temperament and inclination, Picasso embodied a radical renewal that transcended geographic and cultural boundaries. With his Blue Period and subsequent Rose Period, he blended intimate narrative and social empathy, foreshadowing the plastic revolutions to come. Soon after, alongside Georges Braque, he would pioneer Cubism, one of the most innovative movements of the 20th century, embarking on a constant reflection on the nature of representation.

Picasso’s Spanish roots never lay dormant. Andalusian culture, the vibrant colors of his homeland, traditional festivities, and the world of bullfighting — which fascinated him since childhood — continued to emerge throughout his artistic evolution. Think of his recurring figures of toreadors and harlequins, iconic elements he loved to rework with modern sensibility.

At the same time, contact with the French school and international avant-gardes allowed him to blend color and form, sign and spatial structure. Drawing inspiration from Cézanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh, and Matisse, he forged original compositional solutions and created a hybrid identity: rooted in Iberian heritage, open to cosmopolitan experiment. This duality made Picasso a foundational figure for generations of artists and creators.

Picasso’s path never paused: from Cubist experimentation to later neoclassical expressions, from African and Oceanic art references to astonishing stylistic freedom. Yet this was no fragmentation. Rather, he moved like a researcher, testing many avenues to redefine the function of the image.

His expansive repertoire redefined notions of perspective, composition, and volume. A fragmented portrait across multiple planes, a still life reduced to essential geometry, or a mythological scene reimagined with contemporary flair — all reflect his ongoing dialogue between past and future. This creative fertility reveals his will to experiment without succumbing to any single stylistic label.

The exhibition “Picasso the Foreigner” stems from a desire to interpret his work through the lens of his foreign status, though he remained tethered to his roots. Entering France as a young talent, Picasso lived and worked in a kind of voluntary exile. His Spanish passport and Mediterranean identity intertwined with the challenges of Parisian salons, avant-garde currents, and the broader European cultural scene.

His relationship with “otherness” was not only geographical. Though welcomed by the avant-garde, Picasso remained an outsider — free from rigid labels and definitions. This dual position — both within and outside French society — enabled him to observe reality critically and overturn conventions. The exhibition emphasizes how the energy of cultural exchange nourished his poetics, prompting viewers to reflect on identity, belonging, and hybridity.

Picasso’s first Parisian experiences date back to the early 1900s, when the French capital was the epicenter of artistic innovation, frequented by Modigliani, Soutine, and Chagall. In this environment, Picasso connected with Montmartre and Montparnasse intellectual circles, engaging in fervent exchange.

The École de Paris was not a unified movement but a constellation of tendencies united by their quest for new expression. Without adhering to a fixed program, Picasso drew from this scene a dynamic energy that fueled works blending classical heritage and daring innovation. His collaboration with Braque proved critical, allowing them to dismantle and reconstruct the figure: anatomy became a puzzle of planes offering simultaneous viewpoints.

In France, Picasso didn’t just receive cultural hospitality; he elaborated it uniquely, sometimes subverting prevailing aesthetics. Over time, he engaged in a dialectical relationship with French art circles, becoming paradoxically emblematic of Parisian modernity. Yet he remained conscious of his Spanish roots and his emotional distance from French culture.

His portraits of intellectuals, friends, and partners reflect his affinity with Paris’ “foreign elite” — artists from across Europe and beyond. Picasso welcomed diverse influences: African and Oceanic art notably shaped his geometric forms and spatial decompositions. This embrace of the “Other” became central to his poetic vision.

The exhibition layout follows a thematic structure that traces Picasso’s cultural and inner journey. Distinct sections examine the crucial phases of his production — from his early days in Paris to international acclaim. The curatorial approach shows how Picasso’s sense of estrangement and intellectual freedom fueled experimentation, generating works that have become icons of the 20th century.

The selection includes paintings, drawings, sculptures, and prints loaned from major museums worldwide. Some rarely exhibited works provide insight into Picasso’s technical mastery. Visitors navigate a harmonic dialogue across different periods, offering a chronological yet fluid narrative of his stylistic transformations.

It comes out positively conducive to the visitors across the capitol themes that mettono in Luca como la condizione di “straniero” si rifletta nelle opera di Picasso. One of the first environments if it concentrates the blue phase and the subsequent pink phase, combined with intense attention to human conditions. In these words, interest emerges in the marginal figures and in the interior of the souls, with emotive tones and great suggestions.

Continuing, the whole story shows the moment of the birth of Cubism, where the fragmentation of the form riflette a new way of revealing reality. Here, the visitor proceeds from documents, photographs and operations that testify to Picasso’s rapport with the Parisian environment, illustrating his participation in the show, artistic salotti and editorial adventures. There is no space dedicated to all successive experiments, which spaziano delle sculture in ferro battuto alle ceramiche, showing a Picasso always in motion and mai chiuso in a single expressive code

Among the standout pieces featured in the exhibition are several preparatory drawings that offer a glimpse into Picasso’s “workshop,” demonstrating his mastery of line from his earliest anatomical studies. Examples of sketches for monumental works, such as some studies for “Guernica”, reveal the intense design process behind the composition, even though the final masterpiece is not necessarily on display.

The exhibition path also includes some unpublished sculptures, the result of experimental research conducted between the 1930s and 1940s, a period during which the artist explored new materials and techniques. These creations highlight Picasso’s deep curiosity in assembling everyday objects, transforming them into sculptures charged with expressive power. Such pieces rarely appear in exhibitions, making this section particularly interesting for those wishing to discover lesser-known aspects of his work.

The visit to the exhibition is more than just a journey into the avant-garde of the twentieth century. On the contrary, it offers the valuable opportunity to reflect on the dynamics of cultural identity, the power of art to transcend national borders, and the many facets of an artist who persistently questioned traditional canons with renewed energy. The setup interacts with the monumental context of Palazzo Cipolla, juxtaposing Picasso’s modernity with historically significant spaces, thereby creating a striking contrast.

The artist, in fact, stands at the center of a narrative that goes beyond painting, touching on issues of politics, society, and expressive freedom. Picasso, a “citizen of Paris” who never abandoned his Spanish identity, becomes almost an emblem of the modern condition in which identity and “otherness” coexist in fruitful tension. In an era where the migration of ideas often takes center stage, his figure resonates as both timely and universal.

A significant aspect of this exhibition is its educational approach, designed for a broad audience. The explanatory texts, multimedia installations, and direct comparisons between works from different periods help visitors reconstruct the key stages of Picasso’s artistic journey. However, this is not a simplified reading: the curators encourage critical observation, prompting viewers to recognize analogies and contrasts between paintings and sculptures.

In this sense, the exhibition is an excellent opportunity for in-depth study for scholars and art history enthusiasts, but also a learning moment for anyone wishing to approach Picasso’s work with awareness. Thanks to a careful selection of documents and the use of interactive educational tools, it becomes evident how his research helped redefine the visual codes of the 20th century, generating an impact that continues to inspire artists and movements today.

The critical value of this exhibition lies in its ability to explore the various “faces” of Picasso, without reducing him to the stereotype of the “misunderstood genius” or the “mad” artist who disrupts order. In reality, his career was shaped by intense dialogue with tradition, exchange with contemporary artists, and a drive for renewal that pushed him to experiment with multiple genres.

Through a presentation method that highlights both the human and professional sides of Picasso, the exhibition underscores his continual questioning of what it means to represent the visible and inner world. Emblematic are the portraits of friends and acquaintances, often deconstructed into multiple perspective planes, suggesting the idea of a reality that is never singular. Or the still lifes that, beyond their fascination with geometric breakdown, offer reflections on how seemingly humble objects can assume symbolic meaning. These insights generate a deep respect for the legacy of an artist whose language continues to surprise.

The choice to host this exhibition in the city of Rome takes on a particular significance. Long a crossroads of cultural influences, the Italian capital provides the perfect backdrop to reflect on an artist who, while deeply tied to Spain and France, embodies a universal spirit. The museum’s rooms welcome Picasso’s works in a context that balances historical resonance with the need to promote twentieth-century avant-gardes.

Walking among canvases and sculptures surrounded by the atmosphere of Baroque and Renaissance Rome highlights, by contrast, the contemporaneity of Picasso’s forms. It is a fruitful dialogue between different moments in art and culture, capable of sparking reflections both on the historical role of art cities and on their current ability to foster innovation. In this perspective, the exhibition becomes a must-see for understanding the reciprocal influences that shaped Europe’s aesthetic landscape in the last century.

Moreover, Picasso’s figure seems especially fitting in a place like Rome, where the layering of different eras shows how art is not only a witness of a distant past but also a laboratory where ideas from distant places and times are fused and reworked. The presence of the Spanish artist, a “foreigner” in France and now a guest in the Eternal City, reinforces this perception, renewing the concept of cultural exchange that has been fundamental to so many artistic evolutions in the Old Continent.

To fully grasp the importance of the exhibition, it is worth recalling some central stages of the path that took Picasso from Málaga and Barcelona to the heart of the Parisian scene. In the Catalan city, Picasso was educated under the traditional academies, engaging with figures like Santiago Rusiñol and Ramon Casas, who encouraged him to pursue a highly innovative path. From the Els Quatre Gats circle, a legendary place of intellectual exchange, he took his first steps towards a painting increasingly freed from conventions.

His arrival in Paris at the turn of the century was driven by a desire to experience the creative ferment animating the French capital. There, he immersed himself in bohemian neighborhoods, met writers and patrons, and took part in discussions on Impressionism and new post-impressionist trends. In a short time, he established himself as a protagonist of an avant-garde destined to disrupt the traditional structures of European art. One need only think of works like “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon”, where the reinterpretation of African and Iberian models merges with Parisian innovation. Although that painting is not included in this exhibition, its influence pervades many of the works on display, all sharing the idea of deconstructing reality to reconstruct it in new forms.

Between 1907 and 1914, Cubism took center stage in the European cultural landscape, with Picasso and Georges Braque as its principal architects. Unlike other movements, Cubism lacked a rigid theoretical manifesto, instead developing through daily painting practice and constant exchanges between the two artists. The deconstruction of objects, the abandonment of Renaissance perspective, and the use of reduced tonal ranges focused attention on form and visual perception rather than realism.

The reciprocal influence between Picasso and Braque is evident in works that are sometimes difficult to attribute to one or the other due to their stylistic closeness. In the Roman exhibition, the significance of this collaboration is examined through a series of paintings and works on paper illustrating the gradual transformation of figures into geometric structures. The later divergence between the two artists is also highlighted—when, after the Great War, Picasso rediscovered classical models, while Braque pursued a more subdued Cubist evolution.

Although “Picasso the Foreigner” does not aim to be an exhaustive chronological overview, it still highlights the moments when the artist tackled political and social issues. In particular, during the Spanish Civil War, Picasso was deeply affected by the events in his homeland: the creation of “Guernica” (1937) is the most striking example, even though the monumental painting is not part of the current exhibition.

At the same time, the tensions of the First and Second World Wars influenced his worldview, prompting him to reflect on themes of violence, suffering, and human dignity. This aspect emerges in allegorical works where Cubist deconstruction is not merely a formal exercise, but a means of expressing a sense of dramatic precariousness. It is worth noting how his condition as a foreign artist, even after settling in France, did not prevent him from criticizing the war and totalitarian regimes.

In this sense, the Roman exhibition presents a politically aware Picasso, capable of conveying in his paintings and sculptures an expressive urgency that transcends national borders. His interest in formal experimentation thus intersects with reflections on the major events of his time. Visitors will notice how Picasso’s poetics retain a profoundly humanistic spirit, rooted in the belief that art can serve as an emotional and moral testimony.

Examining the innovative force of Picasso, it becomes clear how his legacy influenced not only the painters and sculptors of his era but also subsequent generations. The idea of an art that constantly questions visual conventions paved the way for global movements—from Surrealism to Abstract Expressionism, to the neo-avant-gardes of the post-war period.

Throughout the 20th century, artists such as Francis Bacon, Willem de Kooning, and Jean-Michel Basquiat were inspired by Picasso’s synthesis of figuration and abstraction, and by his bold approach to breaking down subjects. The exhibition brings this legacy to light, inviting visitors to trace the path of an artist who never ceased to revolutionize his technique while maintaining a passionate gaze on life. This coherence between experimentation and depth of vision remains one of Picasso’s most enduring contributions to contemporary art.

Many episodes in Picasso’s biography demonstrate his incredible continuity in production: despite stylistic differences, constant experimentation, and changes of residence, the artist maintained a common thread in his total dedication to the act of creation. This attitude was reflected in a continuous dialogue between tradition and innovation: at times, he would adopt classical compositional modes, only to deconstruct and reconstruct them according to new rules.

This process of continuous transformation still makes his work accessible to multiple interpretations. On one hand, Picasso is a modernist interpreter, ready to break academic canons. On the other, he shows an almost “archaeological” passion for historical models—Greek, Iberian, Renaissance—which resurface in unexpected moments. In this sense, the artist becomes a trait d’union between the centuries, showing that modernity is not a total rupture, but an unceasing evolution of forms and meanings.

The event also addresses the issue of the personal relationships that marked the Spanish master’s journey, particularly during his time in France. His romantic relationships correspond to distinct pictorial cycles in which the artist both celebrates and transfigures his muses. In the female figures depicted in Cubist mode, for example, one perceives a wide range of emotions, from passion to turmoil and fascination.

His close circle included writers and patrons who supported his work, such as Gertrude Stein, as well as contemporary artists with whom he engaged in intense, at times conflictual, dialogue. These interactions gave rise to moments of great fertility: consider his collaboration with Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes or the influence Jean Cocteau had on his stage designs. In any case, Picasso’s nature remained independent: he built his career without binding himself permanently to a group or manifesto, preferring an autonomous path that aptly reflects the theme of “being a foreigner” in a non-native land.

Another fascinating aspect of Picasso’s work, highlighted in the exhibition, is the variety of languages he explored, from painting to sculpture, from ceramics to printmaking. His relentless curiosity led him, especially in maturity, to approach techniques he had previously seldom explored. Working with sculpture did not mean abandoning the two-dimensionality of canvas: on the contrary, it was an opportunity to extend his investigation into how to represent space and give shape to volumes, sometimes constructed from found objects.

In ceramics, at studios in the south of France, he developed another front of artistic expression, creating plates, vases, and painted tiles, often decorated with bull motifs, doves, or faces reinterpreted through a Cubist lens. These works, long considered “minor” compared to his more famous canvases, are today re-evaluated by critics, who recognize in them the same experimental brilliance that defines Picasso’s entire trajectory. The exhibition features several examples of these experiments, confirming how the artist’s vocation was deeply rooted in materiality as well as in ideas.

Examining the entirety of Picasso’s work reveals the profile of a visionary who escapes any strict classification. A foreigner in France, but also a foreigner with respect to any preconceived label, Picasso embodied the freedom of the modern artist to the fullest. Barriers—national, technical, or conceptual—always served as stimuli for him to seek new solutions, as if the creative process were an eternal crossing.

This is why his figure continues to exert such enduring fascination: the universal scope of his research, his ability to dialogue with history and anticipate future trends make him a unique case. Those who step into “Picasso the Foreigner” embark on a journey that is not only a temporal path through the 20th century but also a reflection on how art can serve as a symbolic passport, capable of uniting people and cultures under the banner of creativity.

Tickets are no longer available.

Your opinions and comments

Share your personal experience with the ArcheoRoma community, indicating on a 1 to 5 star rating, how much you recommend "Picasso the Foreigner"

Similar events